Amyloid beta proteoforms and Alzheimer’s Disease – Applications of proteomics in neuroscience

Tyler Ford

February 27, 2025

Alzheimer’s disease is incredibly complex, difficult to diagnose, and difficult to treat. It was traditionally diagnosed postmortem through the identification of amyloid beta plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles in the brain. More recently, researchers have discovered they can diagnose live patients by imaging plaques and tangles in the brain and by measuring tau and amyloid beta biomarkers in cerebral spinal fluid and the blood. Aggregates of amyloid beta and tau have been firmly associated with cognitive decline, but there is still much to learn about Alzheimer’s development and progression. This includes but is not limited to:

- The causal links between aggregate formation or clearance and cognitive decline

- The ties between amyloid beta and tau

- The mix of pathologies that lead to aggregate formation

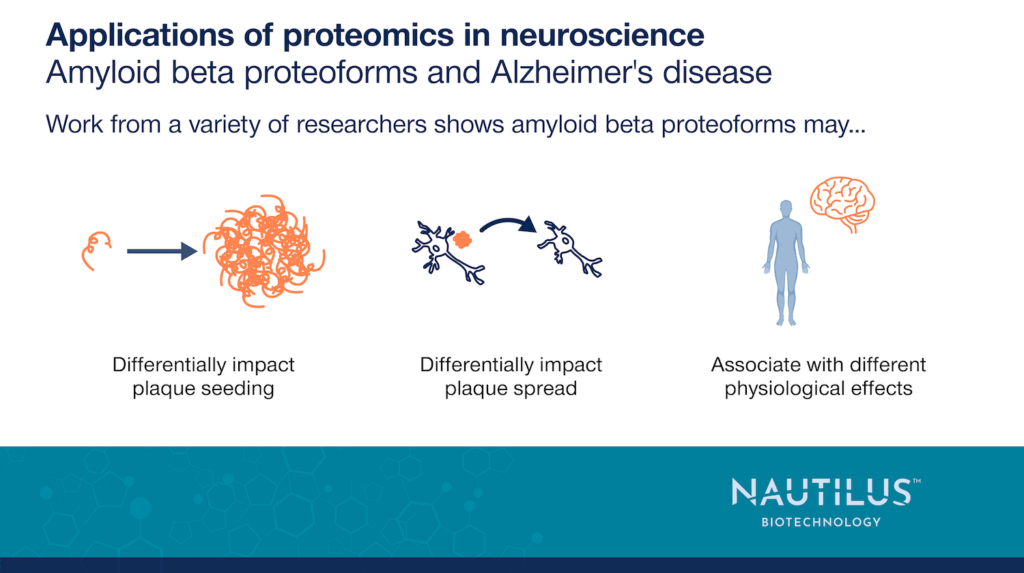

What has become clearer over the last few years is that aggregates of amyloid beta and tau are heterogenous mixtures. Not only are there many proteins in these aggregates (Xiong et al., 2018, Wang et al., 2005, Cardoso Ferreira et al., 2023), but the amyloid beta and tau molecules within them are composed of many discrete proteoforms (molecular variants of each protein). As we’ve discussed on this blog, tau proteoforms may arise in a specified order and may differentially contribute to Alzheimer’s pathology. Understanding these contributions may be crucial to understanding Alzheimer’s. In this post, we provide a brief look at work showing that enhanced understanding of amyloid beta proteoforms may be critical to understanding Alzheimer’s disease as well. This is not an exhaustive review of the literature but nonetheless highlights the important role amyloid beta proteoform research may play in the battle against Alzheimer’s.

Diverse amyloid beta proteoforms in the Alzheimer’s brain

All the studies discussed here make it clear that amyloid beta comes in diverse forms, but Wildburger et al., 2017 directly assessed this diversity in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. They used mass spectrometry to investigate proteoforms found in amyloid beta plaques and discovered 26 different amyloid beta proteoforms with variable combinations of N-terminal truncations, C-terminal truncations, and post-translational modifications (PTMs) in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. They additionally identified trends in the differential abundance of amyloid beta proteoforms between soluble and insoluble amyloid beta fractions. While these investigators studied a small number of Alzheimer’s patients (N=6) and only looked at post-mortem samples, their work highlights the heterogeneity of this single protein in plaques and points to the need to learn more.

This work raises intriguing questions about whether the different amyloid beta proteoforms observed play distinct roles in the seeding and development of plaques. These proteoforms may also be associated with different downstream physiological effects. The papers referenced in the examples below begin to answer such questions.

Watch Nautilus Senior Director of Scientific Affairs and Alliance Management Andreas Huhmer discuss a new era of Alzheimer’s research with Sarah DeVos Ph.D. of Curie.Bio

Cell and animal models provide insights into Alzheimer’s development

Given how difficult it is to obtain brain samples from living Alzheimer’s patients, in vitro and in vivo models play a large part in elucidating the impacts and etiology of amyloid beta plaques. Various studies leveraging such models point to differential impacts of amyloid beta proteoforms on aggregate formation and Alzheimer’s pathology.

In 2013, Bouter et al. tested the ability of a variety of amyloid beta proteoforms to form aggregates in vitro and in vivo. They found that different amyloid beta proteoforms aggregate at different rates and have different structures. Of the proteoforms they tested, amyloid beta pE3-42 (which begins with pyroglutamate at what would be position 3 in full-length amyloid beta and ends at position 42) had the highest propensity to aggregate, amyloid beta 4-42 (starting at position 4 and ending at position 42) had the second highest propensity to aggregate, and proteoforms with C-terminal truncations (some of which also had N-terminal truncations) had lower propensity to aggregate.

Furthermore, amyloid beta proteoforms were differentially toxic to primary neurons. Of the proteoforms tested, amyloid beta 1-42, pE3 4-42, and 4-42 lowered cell viability the most. Injecting all the amyloid beta proteoforms tested into the brains of live mice also impaired working memory as assessed by a maze test. Finally, transgenic mice expressing amyloid beta 4-42 and thereby having chronic exposure to this proteoform had decreased hippocampal neuron abundance and impaired spatial memory as assessed by a separate maze test. The effects on memory were also stronger in older mice as compared to younger mice.

Overall, the results in Bouter et al., 2013 show that amyloid beta proteoforms can cause different effects at the molecular and cellular levels and that a specific amyloid beta proteoform can cause detrimental effects in vivo.

Beretta et al., 2024 similarly used biological models to determine how various amyloid beta proteoforms are generated. In their work, they treated iPSC-derived astrocytes with in-vitro generated amyloid beta fibrils consisting of amyloid beta truncated at position 42. These fibrils were taken up by the astrocytes (along with magnetic beads), stored in lysosomes, and truncated further to generate additional proteoforms. Some of these new, truncated amyloid beta proteoforms were excreted in extracellular vesicles and others were released directly into the growth media. Interestingly, the proteoforms inside astrocytes were often N-terminally truncated and formed high molecular weight aggregates that were resistant to denaturation. The authors suggested that these stable proteoforms may be transferred to other cells to seed further aggregate formation. If true, this would be yet another way specific amyloid beta proteoforms can impact disease pathology. It may also be possible to develop novel drugs that target the proteoforms best at spreading between cells and thereby abrogate disease.

In a final example using an in vivo model, Kandi et al., 2023 studied the 5xFAD mouse model which expresses five mutations found in cases of familial Alzheimer’s disease. They monitored the amyloid beta proteoforms produced in this model over time, used hierarchical clustering to put the proteoforms into 3 groups based on expression levels across the study, and determined which proteoforms were found in soluble and insoluble fractions. Those in the insoluble fraction were likely associated with aggregation. One particular group (demarcated as Group 1 in this study) was consistently found in the insoluble fraction and increased in abundance in this fraction with aging. This group contained many proteoforms with N-terminal truncations.

Finally, they also observed differences in the abundance of proteoforms with particular PTMs. For example, amyloid beta pE3-42 increased in relative abundance with age in both the soluble and insoluble fractions.

While causal relationships between proteoforms and dementia were not determined in this work, clear associations between certain groups of proteoforms, amyloid beta fractions, and age once again suggest that amyloid beta proteoforms may have differential impacts on the pathology and trajectory of Alzheimer’s disease.

Amyloid beta proteoforms and clinical trials

Given the association between amyloid beta aggregates and Alzheimer’s, researchers have been developing drugs that clear these aggregates for many years. Indeed, three recently approved drugs, Aducanemab (since discontinued by its developer), Lecanemab, and Donanemab all consist of monoclonal antibodies targeting amyloid beta (Golde and Levey 2023, Zhang et al., 2024). These drugs all clear amyloid plaques and slow, but do not prevent cognitive decline. All also target epitopes found in insoluble forms of amyloid beta:

- Aducanemab: Binds amino acids 3-7 in amyloid beta

- Lecanemab: Binds structures formed by amyloid beta aggregates

- Donanemab: Targets pyroglutamate at position 3 in amyloid beta

These antibodies may slow cognitive decline due to their propensity to bind amyloid beta epitopes associated with plaques as opposed to soluble amyloid beta (Golde and Levey 2023, Zhang et al., 2024). In the future, It may be possible to associate these epitopes with groups of proteoforms that arise during different stages of Alzheimer’s, and it will be interesting to see if one of these drugs (or a new one) ultimately proves best at slowing cognitive decline. Such a result may point to a group of amyloid beta proteoforms as particularly important to Alzheimer’s progression and may spur the development of additional drugs that either clear these proteoforms or prevent their generation. In this way, greater knowledge of proteoforms may help researchers understand the results of these and future clinical trials targeting amyloid beta. They may also point to additional avenues for productive drug development.

As companies like Nautilus develop technologies that can quantify proteoforms, we may gain a much better understanding of Alzheimer’s and many other diseases. Hopefully this understanding will lead to new ways to prevent, treat, and cure ailments of all kinds.

MORE ARTICLES