Using proteomics to personalize medicine across the continuum of care (Part 1)

Tyler Ford

June 27, 2023

For many years we’ve been told that a wave of precision and personalized medicines based on the intricate, molecular details of patient biology is just over the horizon. Unfortunately, except for niche cases like drugs targeting specific mutations in cancer (Morash et al 2018) or genome editing for cancer and rare diseases, this wave has not come.

Biologists have long sought technologies that will make personalized medicine possible and many hoped that advances in genetics and genomics were the key to unlocking this new era. Indeed, new DNA sequencing technologies have revealed genes associated with disease, and full genome sequencing can tell individuals about their potential susceptibility to certain ailments. Yet, genomes do little to inform people about their current health or if their lifestyle choices have increased or decreased their disease risk.

To truly achieve personalized medicine, we need to look beyond DNA and instead focus on the molecular machines that scientists have long recognized as fundamental units of biological activity. We need to look to proteins.

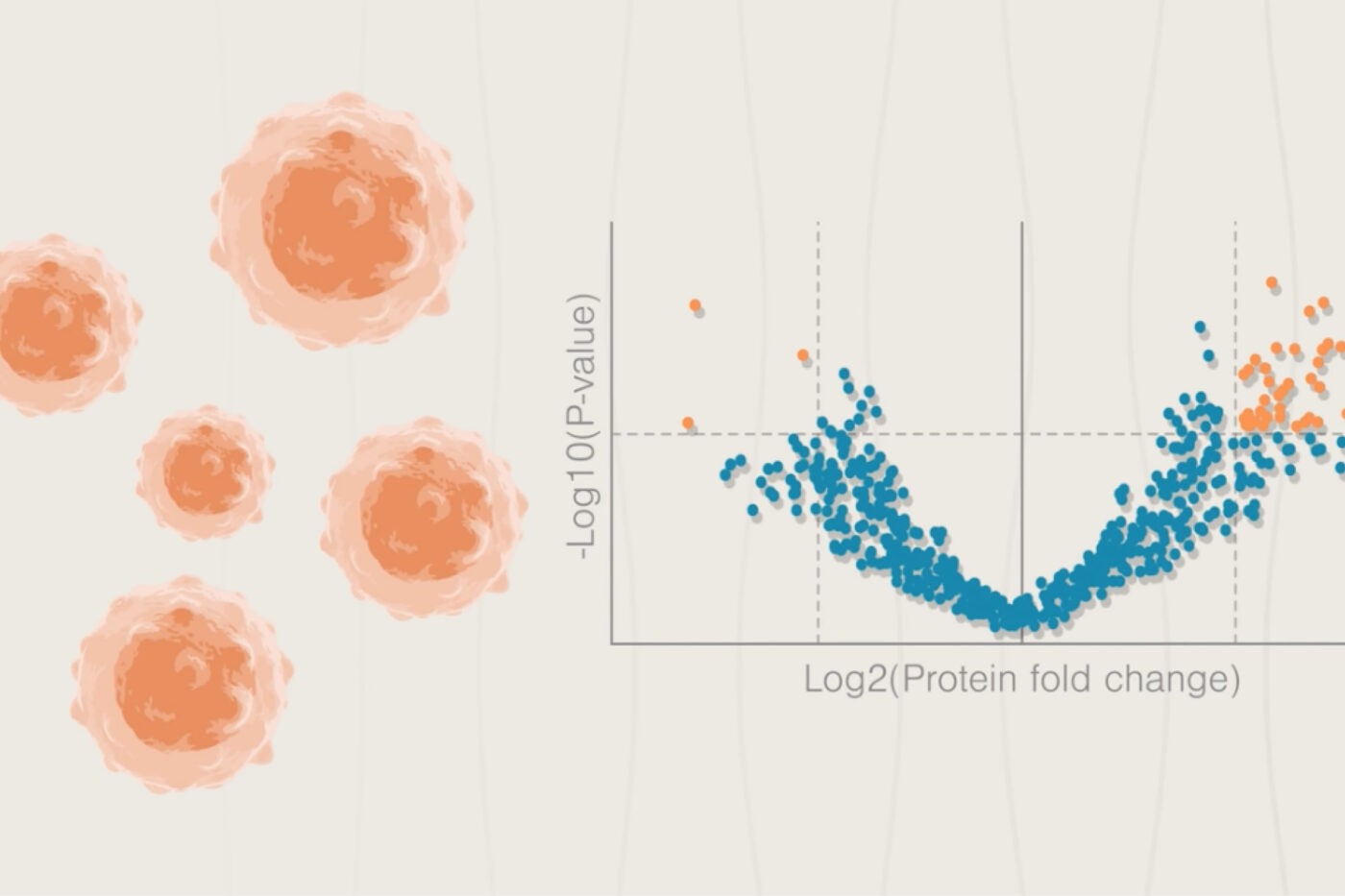

Proteins carry out the vast majority of cellular processes and a cell’s “proteome,” the dynamic composition of its full set of proteins and their associated distribution throughout the cell and body, determines cellular identity, form, and function. “Proteomics” technologies aim to reveal the abundances and locations of all proteins in biological samples right now. The dynamic patterns of these ever-changing proteomes comprise thousands to millions of fluctuations in protein levels and distribution, and can reveal whether we are healthy, sick, or have enhanced potential to become sick.

This is the first post in a two part series covering how caregivers can apply proteomics technologies across the continuum of care. Here, we dive into the ways physicians can use proteomics to establish personalized baseline measures of health and diagnostics essential to establishing when something has gone awry. In a future post, we cover the ways proteomics can improve drug development and forecast changes in patient health.

Want to read the full white paper now?

Personalized measures of baseline health

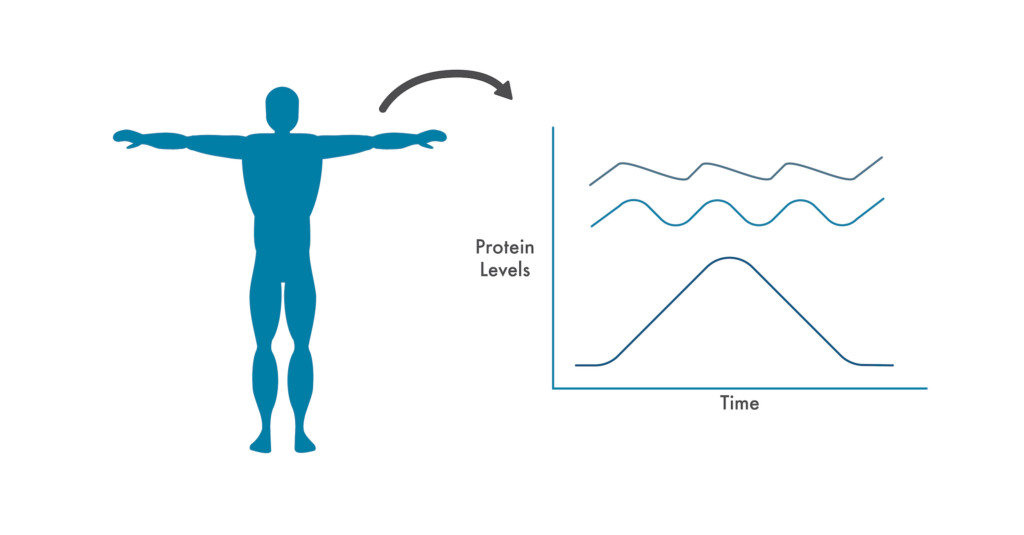

Capturing protein fluctuations when a patient is well provides caregivers with a dynamic baseline indicative of good health.

Physicians often use average health metrics to determine if a patient is sick, but this is problematic because even basic metrics like body temperature can vary significantly from person to person (Obermeyer et al 2017). Every biologist knows that no two cells or organisms behave in exactly the same way. Even a single cell will behave differently in different environments. No matter how hard we try to make measurements in controlled settings, biology is complicated and differences will manifest. To provide patients with more meaningful measures of their health, we need to embrace biology’s complexity and move beyond average population metrics to personalized, time-dependent measures. Proteomics enables us to do so.

By regularly assessing how an individual’s protein levels and cellular distribution change from day-to-day, minute-to-minute and comparing these changes with other measures of health, we can associate particular patterns of protein production with individual patient wellness. Rather than look at crude population measures, physicians can then assess whether a patient’s proteome deviates from a personalized “normal.” In doing so, they can prevent unnecessary worry when other metrics are out of step with population averages but normal for the individual.

Screening for potential problems and pinpointing their causes with diagnostics

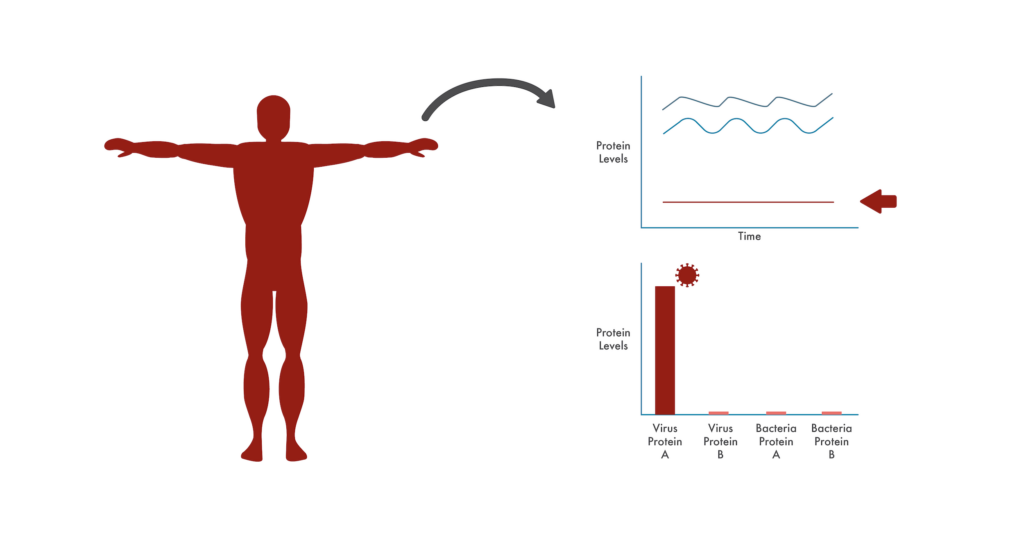

Changes from baseline protein fluctuations can provide caregivers with clues as to the cause of a disease. Refined measurements of additional proteins (like viral and bacterial proteins) can diagnose the cause of the disease.

With a proteomic baseline in place for an individual patient, a physician has a holistic way of screening that patient for many ailments at once. Under the current status quo, many men and women regularly undergo specialized screens for common diseases. We have mammograms for breast cancer, colonoscopies for colon cancer, glucose tests for diabetes, and much more. These screens are useful because they help physicians detect diseases early – when they can be most effective. However, screens can be expensive, anxiety inducing, and even physically harmful.

With proteomics, on the other hand, physicians have the potential to screen for protein changes associated with many different diseases at once without worrying the patient about a particular disease when doing so is not necessary. If a physician noticed that a patient began to deviate from their personalized proteomic baseline, they could dig into the data to determine which specific proteins were altered from the baseline. There may be known associations between these altered proteins and a particular disease or, if enough patients regularly measure their proteomes, researchers could begin linking additional changes with specific diseases. In this way, proteomic measurements taken at a standard visit to the clinic could automatically act as screens for a wide variety of diseases and show whether their proteomes are being impacted in a comprehensive way. This would get patients the treatments they need quickly and improve therapeutic effectiveness.

This type of proteomic screening could also complement other diagnostics measurements. For example, caregivers might see that proteins involved in responding to viral infections are surging. To pinpoint the precise problem, they could order further diagnostic tests that look for viral proteins indicative of specific viruses. Rather than prescribing a treatment based on symptoms alone, proteomics can guide physicians to the most useful diagnostic tests, avoid wasting time, and give them the confidence to prescribe therapeutics that precisely target a patient’s illness.

In the next post in this series, we’ll discuss how researchers and clinicians can use next-generation proteomics to develop effective treatments, use them, and forecast changes in patient health.

Want to read the full white paper now? Download “Using proteomics to personalize medicine across the continuum of care” here.

MORE ARTICLES